Giving Robots a Sense of Touch: Tactile Sensing for MANiBOT

Robotic manipulation systems are fast, repeatable, and increasingly capable, but compared to humans they remain surprisingly “numb.” While vision systems allow robots to see their environment, they lack many of the rich sensory cues people rely on when handling objects, particularly the sense of touch. This limitation confines many robots to highly controlled settings, manipulating objects with simple geometry and predictable behaviour.

The MANiBOT platform aims to move beyond these constraints. Designed to operate in dynamic, real-world environments alongside humans, MANiBOT must handle objects of varying size, shape, weight and material, often in cluttered or partially occluded settings. To meet these demands, robots need more than just eyes; they need a sense of touch.

MANiBOT’s Task 6.1, led by the University of Bristol, addresses this challenge through the development of high-resolution artificial tactile sensors. These sensors allow the MANiBOT platform to physically “feel” its interactions with the world, enabling safer, more reliable, and more adaptable manipulation , even when visual information is limited.

Vision-based perception alone is often insufficient for manipulation. Objects may be partially hidden, reflective, deformable, or visually ambiguous. Even when an object is clearly visible, vision struggles to capture what happens at the moment of contact, for example, how firmly an object is grasped, whether it is slipping, or how it is oriented once in the gripper.

Humans instinctively solve these problems using touch. We adjust our grip force, feel when an object begins to slide, and infer shape and orientation through contact. Task 6.1 brings these capabilities to MANiBOT by providing continuous, local feedback directly from the contact interface between robot and object.

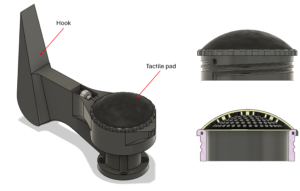

The University of Bristol developed two bespoke tactile sensors tailored to MANiBOT’s distinct use cases. Both designs build on the widely recognised TacTip sensor concept, which uses a soft, deformable skin to translate physical contact into rich sensory data.

Each sensor consists of a compliant outer skin whose inner surface is populated with a dense array of small, flexible markers. When the sensor makes contact with an object, the skin deforms and the markers move accordingly. A compact internal camera observes these movements, producing images that effectively encode information about the contact. Rather than relying on traditional force sensors, these “tactile images” are interpreted using machine-learning models. From them, the system can infer meaningful properties such as contact location, orientation, and applied force.

Advanced multi-material 3D printing was used to manufacture the sensors, enabling precise control over geometry, stiffness, and durability. This allowed each design to be closely matched to the physical demands of its intended environment.

For the supermarket use case, the robotic platform must handle a wide variety of objects, ranging from rigid boxes to soft, irregularly shaped items, demanding a strong emphasis on precision in manipulation. To support this, a fingertip-style tactile sensor was developed that can be retrofitted to common off-the-shelf grippers, in this case a Robotiq 2F-140. This design incorporates two tactile interfaces: a larger internal sensing surface optimised for pinching and grasping objects, and a smaller sensor at the fingertip designed for pushing, probing, or stabilising items during manipulation. Together, these provide rich tactile feedback throughout the handling process.

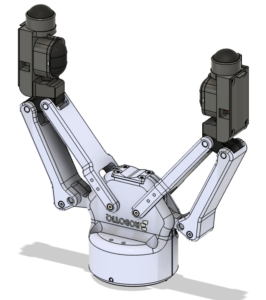

In contrast, the airport use case involves much larger, heavier, and more uniform objects, such as luggage. Here, robustness and durability are prioritised over fine precision. To meet these requirements, a large-area tactile pad was developed and mounted at the wrist of each robot arm. Manufactured using specialised 3D printing techniques, this sensor has a significantly higher stiffness, allowing it to withstand repeated heavy loads while still providing meaningful contact information. Its placement at the wrist enables the MANiBOT platform to sense interactions whilst manipulating bulky items.

At a system level, tactile sensing provides the MANiBOT platform with a new stream of information that complements vision and motion control. By turning raw contact into interpretable signals, the robot gains a basic form of tactile awareness: understanding how it is interacting with the world, not just what it sees. This enables more adaptive behaviour, such as adjusting grip force in real time, detecting unexpected contacts, or continuing operation when visual information is unreliable. Crucially, it also supports safer human–robot interaction by allowing the robot to respond sensitively to physical contact. By equipping MANiBOT with a sense of touch, this work helps bridge the gap between laboratory robotics and real-world deployment, bringing robots one step closer to interacting with their environment with human-like awareness and adaptability.